Many of the New Deal era programs were sunset during and just after World War II, when heavy investment in the engines of war helped to rebound the economy. Many of us share or have been taught a historical memory of the post-War era as a time of relatively widespread prosperity after the economic challenges of the Great Depression.

Hunger, Justice,

and Civil Rights

Eating and Jim Crow

Having grown up in Philadelphia and New York, painter Jacob Lawrence visited New Orleans in 1941 with his wife, fellow artist Gwendolyn Knight. Although Lawrence was an avid student of history who explored Black history in his paintings, his first trip to the Deep South opened his eyes to the absurdity of racial segregation. At this New Orleans restaurant, a flimsy wooden barrier separates the bar into two spaces — one for white people and one for Black people. From the bartender’s point of view, patrons are invisible to one another.

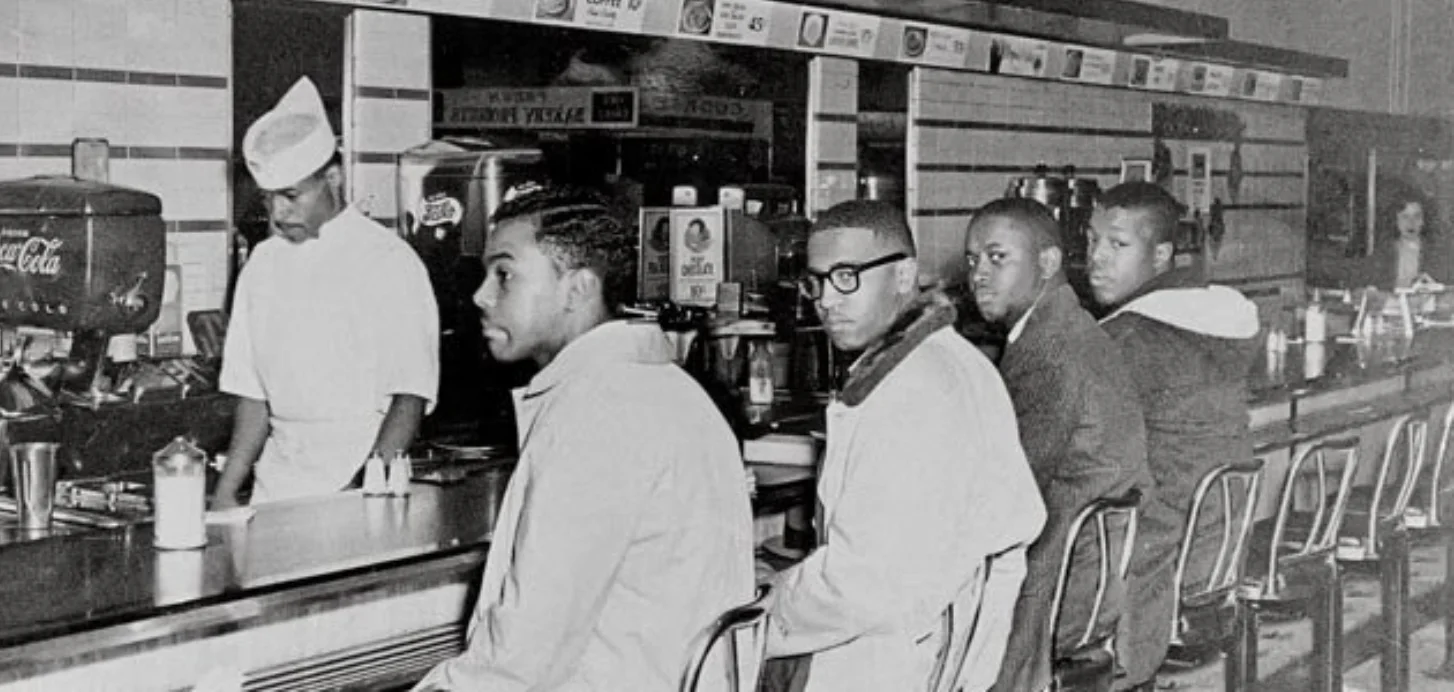

Lunch Counter Student Sit-Ins

Students at North Carolina A&T University centered equal access to food in their advocacy challenging Jim Crow and segregation, organizing “sit-ins” at Woolworth’s whites-only lunch counter. Despite arrests and attacks, their stalwart civil disobedience succeeded in forcing Woolworth’s to grant them full and equal rights in their restaurant within months, and spurred additional, successful sit-ins by students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities in many other Southern cities.

The Fish Wars

Unfulfilled, ignored, and broken treaty obligations cutting off their access to fishing, hunting, and foraging had left Nisqually Tribal members facing severe hunger. In 1963, Billy Frank Jr. took up civil disobedience as a survival strategy, launching “fish-in” protests that gained national media and celebrity attention. By 1974, the courts determined that the Nisqually had a right to one half of the fish harvested from their river, establishing important precedent for future challenges by Indigenous communities.

Counterculture and the Diggers

The Diggers, a leaderless counterculture group in San Francisco, rejected participation in the postwar economy and argued for San Francisco to become a “Free City,” where all necessary resources were shared. Access to food was central to their vision: they served soup and other meals in the parks to anyone who brought a bowl, put up posters letting newcomers to the city know where to find food, and hosted events in pursuit of egalitarianism and social justice.

Fannie Lou Hamer and Freedom Farmers

Fannie Lou Hamer forged a new path for rural Black people to escape poverty and hunger. In 1960 she set aside her years of voting rights activism to build an innovative new system — cooperative farming. Her Freedom Farm Cooperative, which enabled Black families to own and cultivate land communally, trading work on the farm for a share of the crops they produced, fed 1,600 families by 1972 and became the prototype for the modern food banking system.

LaDonna Redmond and Monica M. White, Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement (UNC Press, 2018).

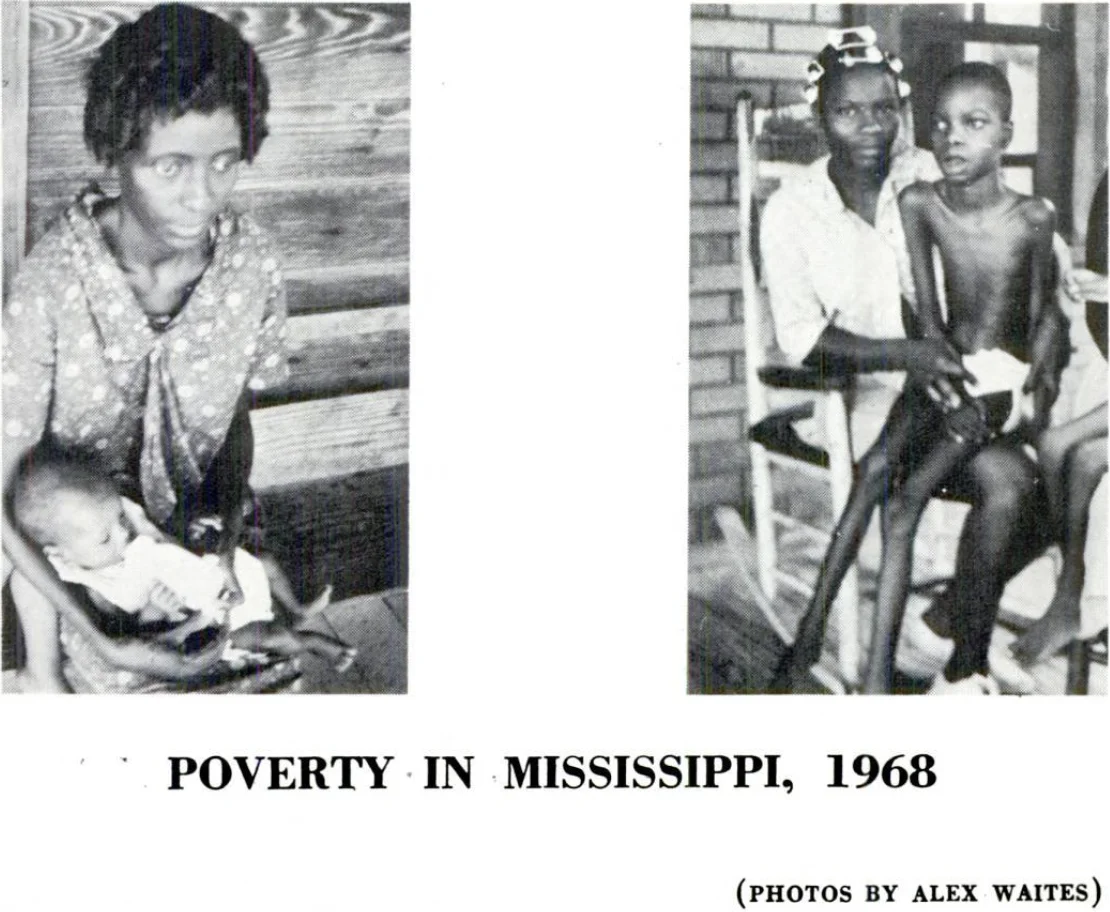

Advocacy Through Imagery

In 1968, the NAACP’s monthly magazine, The Crisis, ran a series of shocking photographs about hunger in the Mississippi River Delta. The previous year, the NAACP had opened three emergency relief centers in the region, but such emergency measures were not enough to abate the crisis. Many families did not qualify for food stamps, forcing some parents to abandon their families so that their children could eat. These images of mothers and their starving children sent a clear message to readers that the famine-like conditions in the Delta were urgent.

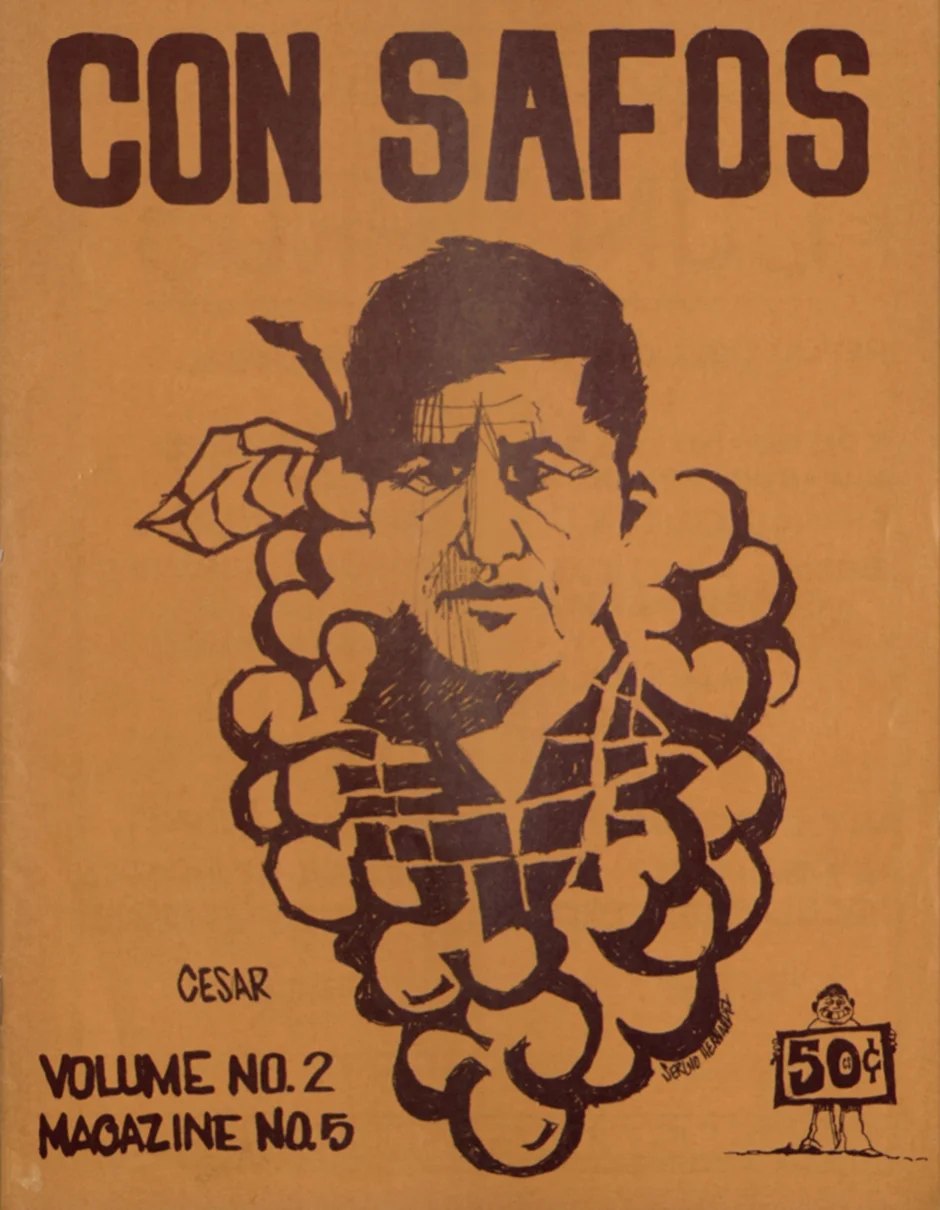

Cesar Chavez’s Fast for Nonviolence

In Delano, California, unionized grape pickers — mostly of Filipino and Latino descent — and other farm workers were among the most food insecure in America. Cesar Chavez, a farmworker and leader of the United Farm Workers, began a 25-day “love fast” on the traditional Feast of St. Valentine in 1968. Every night, an ecumenical array of spiritual leaders led religious services. Senator Robert F. Kennedy attended the final night, a Mass of Thanksgiving that opened with a Jewish prayer. Priests broke bread and the fast ended with communion served from an altar on a flatbed truck.

Walk for Decent Welfare

By the time the Walk for Decent Welfare reached Washington, DC in 1968, it had spanned 150 miles, touched dozens of cities, and had been joined by some 6,000 people. The protesters — mostly women of color and their children — demanded their roles as caregivers be recognized, valued, and financially supported, highlighting the vitally important need for meaningful government programs to feed families, and showcasing the barriers at the intersection of racism, sexism, and paternalism in those programs.

Nadasen, Premilla. Rethinking the Welfare Rights Movement (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2012).

Poor People’s Campaign

The Poor People’s Campaign, led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., focused the attention of participants in the Civil Rights Movement on poverty and economic inequality. In 1969, Rev. Jesse Jackson led efforts in Chicago focused specifically on hunger and malnutrition in the city’s Black community, including a march of 2,000 people to the Illinois State Capitol, demanding that the state government declare Illinois a “disaster area” due to reports of starvation. Hundreds of people protested for months until the state government promised a substantial $5.4 million boost in funding for school lunch programs.

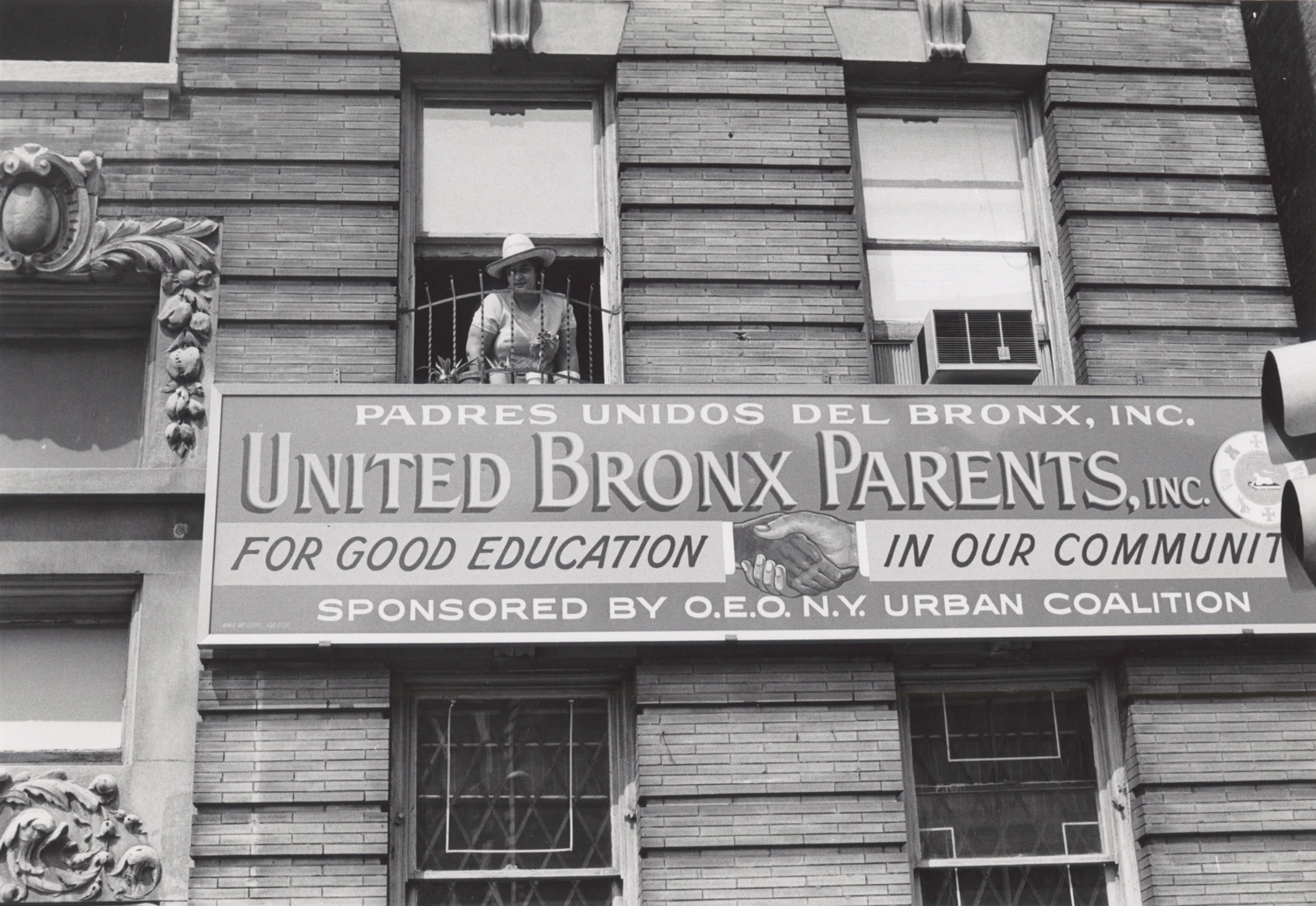

United Bronx Parents

In the mid-1960’s, parents from low-income Black and Puerto Rican communities of New York City organized against racism in the school system. United Bronx Parents focused first on improving the school lunch program. Led by founder Evelina Antonetty, parents drove to Washington, DC with two trucks filled with uneaten, unwanted lunches, dumping the trash bags on the doorstep of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). As a result, USDA invited the parents to directly administer their community’s school lunch program, allowing them to make decisions about vendors and food in a way that best suited their community’s needs.

Lana Dee Povitz, Stirrings: How Activist New Yorkers Inspired a Movement for Food Justice, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019): 86.

Doris Derby

One of the most prolific photographers of the Civil Rights Movement, Doris Derby, stood out as a Black woman at a time when most of her peers in the field were white men. Her unique perspective — and the access her position as an organizer and educator for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee provided — allowed her to capture intimate portraits of Black life and to document the variety of ways local organizations sought to empower Black people, from voting, to adult education, to health care clinics.

and Civil Rights

The years after World War II saw the emergence of struggles for equity and civil rights in America, including the movement for women’s rights and the Black freedom struggle. The Civil Rights Movement had won major legislative victories that ended legal segregation and established equal protection under the law. But by the late 1960s, new movements emerged borne of revolutionary notions of Black Power, Women’s Liberation, Red Power, and Chicano Power, demanding deeper social and economic transformation.

Organizing, peaceful dissent, and art were used to try to persuade the government to respond to hunger, and to include all who struggled in that response. Community responses to hunger emerged, many of which presaged the current charitable food system today. But it was the robust and powerful government response that signaled a possible end to hunger in America.

Rising activism opened space for the pursuit of broad and sweeping change in the post-war era, including government interventions on the issue of hunger. Explore the map to see various ways that community organizers reframed hunger as an urgent matter of economic justice and racial equity and access to food as an essential right of all Americans — one for which the federal government had particular responsibility.

Museum Map

WISHING

TREE

The Proof is in Our History

- 1.Welcome

- 2.Welcome

- 3.The Age of Mass Migration - Landing

- 4.The Age of Mass Migration - Main

- 5.Immigration from Europe

- 6.Early Activists

- 7.The Great Depression

- 8.Charity Is Not Enough

- 9.Hunger is No One's Fault

- 10.The New Deal

- 11.Political Compromises

- 12.An Unequal Recovery

- 13.Back Door Exclusions

- 14.Hunger, Justice, and Civil Rights - Landing

- 15.Hunger, Justice, and Civil Rights - Main

- 16.The Walk for Decent Welfare

- 17.Televising the War on Hunger - Landing

- 18.Televising the War on Hunger - Main

- 19.Hunger in America

- 20.The Great Society

- 21.Bipartisan Consensus

- 22.Nixon Works to End Hunger

- 23.The Unmaking of the Great Society - Landing

- 24.The Unmaking of the Great Society - Main

- 25.President Reagan

- 26.The Myth of the Welfare Queen

- 27.Cementing Stereotypes into Policy

- 28.A New Bipartisan Consensus

- 29.Where We Are Now - Landing

- 30.Where We Are Now - Main

- 31.The Pandemic

- 32.Patching our Safety Net

- 33.Our Wish for the Future

- 34.End tour

Welcome to the Hunger Museum, a virtual project of MAZON.