The result of nearly a decade of government investment into ending hunger was powerful: we were able to reduce hunger to just 3% of the American population. That’s as close to a functional end to hunger as we’ve ever achieved – fewer people going onto the food stamps rolls, and supported robustly enough to stabilize once they were there.

So, how did we climb from just 3% of Americans struggling with hunger to a shocking 13.5% of Americans struggling – fully 47 million Americans? What happened?

Government Cheese

Since 1977, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) regularly purchased surplus dairy products to protect the milk industry and dairy prices. Fresh milk, powdered milk, butter, and cheese were stockpiled in enormous quantities. By 1981, only a little more than one-quarter of U.S.-made cheese was purchased and USDA had no plan for the excess food. President Reagan seized the opportunity, giving a speech about so-called “government cheese” and announcing that those who lost their food stamps would be eligible to receive it through local charity organizations.

TEFAP and the Charitable Food System

In 1981, President Reagan slashed the budgets of assistance programs for low-income households, cutting billions from the Food Stamp Program. Fearful that these cuts would leave Americans starving, Congress passed the bipartisan Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), which expanded the distribution of surplus agricultural products to the states. States then passed TEFAP products along to eligible agencies — mostly private charities — which fundamentally shifted the responsibility of food aid from the government to private charitable organizations.

While these private charities provided important emergency services to those facing hunger, the nature of TEFAP restricted funds for administrative support, so many of the agencies relied on the labor of volunteers and struggled to meet their communities’ growing needs. And because TAFAP did not include protections against discrimination, some organizations would turn hungry people away if they showed signs of substance use, if they did not speak English, or if they were otherwise deemed to be “suspect.” Some religiously affiliated organizations would evangelize before providing food.

The Farm Debt Crisis of the 1980's

In the early 1970’s, demand for U.S. agricultural products abroad surged. Farmers took on massive debts to buy more land to meet the demand. But reduced international prices and rising interest rates combined in the 1980’s, forcing down profits and the value of farmland at the same time. American farmers now struggled to feed their own families.

Since asset limits and distance prevented many farm families from accessing food stamps, rural communities organized food banks and mutual aid. Farmers organized tractor-cades to draw attention to the scale of the crisis and call for a moratorium on farm foreclosures. In the late 1980’s, Congress finally authorized new policies to stabilize the farm economy, but to many farmers, these legislative interventions were too little too late.

Hal Hamilton and Ellen Ryan, “The Community Farm Alliance in Kentucky: The Growth, Mistakes, and Lessons of the Farm movement of the 1980s,” in ed. Stephen L. Fisher, Fighting Back in Appalachia: Traditions of Resistance and Change (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993), 129. See also Gilbert C. Fite, “The Farm Debt Crisis of the 1980s: A Review Essay,” The Annals of Iowa 51, no. 3 (1992): 289.

Housing and the “New” Homelessness

In 1987, Congress passed the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, which removed the requirement that applicants to the Food Stamp Program provide a permanent address, reflecting a new consensus that the growing numbers of unhoused Americans deserved nutrition benefits. As American businesses sent production overseas in the 1980’s, a wave of factory closures left millions unemployed, particularly among communities of color. Demand for low-cost housing surged, but the Reagan administration had ended the federal programs that funded public housing. And nationwide, the government reversed policies that required institutionalization of those suffering with substance abuse and mental illness, which forced more people onto the streets and into poverty.

UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy, “The Making of a Crisis: A History of Homelessness in Los Angeles,” Jan. 2021.

No Human Being is Illegal

By the time President Bill Clinton took office in 1992, hysteria surrounding so-called “illegal immigrants” had reached a crisis point. In 1994, President Clinton instituted a series of enforcement measures designed to stem illegal crossings, and voters in California passed Proposition 187 (which was later overturned by the Supreme Court), barring undocumented immigrants from accessing social services.

While most legal immigrants were eligible for food stamps, after 1996, they were barred from receiving most federal benefits until they had been in the country for five years. Food stamp eligibility was later restored for certain legal immigrants, but despite popular claims to the contrary, undocumented immigrants have been — and continue to be — explicitly barred from all federal assistance programs.

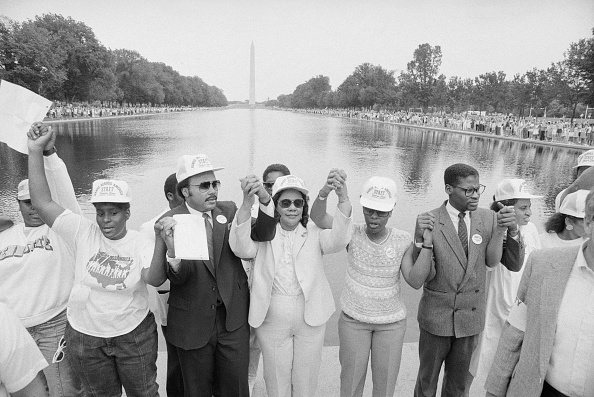

We Are the World

By the mid-1980s, famine in parts of Africa inspired European musicians to form a supergroup called Band Aid, recording a holiday album supporting relief. Inspired by that success, Harry Belafonte — a Black singer and leading figure in the Civil Rights movement — recruited Michael Jackson, Lionel Richie, and Quincy Jones to write and record “We Are the World” in 1985. The song showcased multiple performers calling for all to “lend a helping hand.” “We Are the World” became the first certified multi-platinum single in American recording history, proving the value of an entrepreneurial approach to charitable fundraising.

Hands Across America

The smashing success of “We Are the World” in 1985 inspired band manager Ken Kragen to arrange another celebrity-studded event for the spring of 1986: “Hands Across America.” Over 5 million people donated $10 each in exchange for a T-shirt and a spot in a hand-linked line stretching all the way from New York City to Los Angeles. This event refocused America’s attention on hunger at home. The children of two homeless families assumed the positions on either end of the enormous human chain, holding hands with celebrities and ordinary people.

Welfare Reform

After campaigning on a promise to “end welfare as we know it,” President Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (often referred to as welfare reform) in 1996. Building on the racist and sexist tropes about struggling Americans cemented in the culture wars of the 1980’s, Representative Newt Gingrich and Congressional Republicans wrote the legislation purportedly to break the “cycle of poverty.” Welfare reform introduced work requirements and time limits on assistance programs like food stamps, as well as a lifetime cap on benefits. Thousands of once-eligible families immediately lost access to benefits, and thousands more were discouraged from applying.

in the Age of Austerity

President Reagan’s Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) led to the large charitable food system we see today. But major economic and political changes at the time left millions of Americans in desperate need of food assistance. While charitable organizations did their best to meet the emergency needs of those facing hunger, they were intended to be a complement to — not a substitute for — the reach and resources of the federal government. The willingness of charitable organizations to step into this breach became a rationale for further shrinking the government’s response to hunger.

The farm debt crisis of the 1980’s accelerated the corporate consolidation of American agriculture. Failed farms were incorporated into ever-larger operations, while other cash-strapped farmers became captive to corporate buyers. Just as in the 1930’s, a “paradox of plenty” emerged of growing agricultural surplus amid increasing food scarcity. The charitable food system became a vent for the resulting massive surpluses.

This exhibit locates the origins of the charitable food system in a series of structural changes in the 1980’s and 1990’s that created new hungry populations who faced new barriers to accessing federal food assistance.

Museum Map

WISHING

TREE

The Proof is in Our History

- 1.Welcome

- 2.Welcome

- 3.The Age of Mass Migration - Landing

- 4.The Age of Mass Migration - Main

- 5.Immigration from Europe

- 6.Early Activists

- 7.The Great Depression

- 8.Charity Is Not Enough

- 9.Hunger is No One's Fault

- 10.The New Deal

- 11.Political Compromises

- 12.An Unequal Recovery

- 13.Back Door Exclusions

- 14.Hunger, Justice, and Civil Rights - Landing

- 15.Hunger, Justice, and Civil Rights - Main

- 16.The Walk for Decent Welfare

- 17.Televising the War on Hunger - Landing

- 18.Televising the War on Hunger - Main

- 19.Hunger in America

- 20.The Great Society

- 21.Bipartisan Consensus

- 22.Nixon Works to End Hunger

- 23.The Unmaking of the Great Society - Landing

- 24.The Unmaking of the Great Society - Main

- 25.President Reagan

- 26.The Myth of the Welfare Queen

- 27.Cementing Stereotypes into Policy

- 28.A New Bipartisan Consensus

- 29.Where We Are Now - Landing

- 30.Where We Are Now - Main

- 31.The Pandemic

- 32.Patching our Safety Net

- 33.Our Wish for the Future

- 34.End tour

Welcome to the Hunger Museum, a virtual project of MAZON.