Ellen Swallow Richards studied chemistry while attending Vassar College, becoming the first woman to graduate with a B.S. from MIT. She continued her chemistry studies as a graduate student, but was refused an advanced degree because of her gender. Richards donated her own money to create the first laboratory devoted to nutrition science at MIT. Richards and her students, many of whom were women, studied the chemistry of food and its impact on the body, publishing their insights in handbooks for women. By working to improve the nutrition and sanitation of American eating habits, Richards pioneered the field of “Home Economics.”

Levine, Susan. “School Lunch Politics: The Surprising History of America’s Favorite Welfare Program.” Princeton University Press, 2008.

In 1890, Ellen Swallow Richards partnered with a fellow home economist to establish the New England Kitchen of Boston. Designed as a model for food safety and sanitation, the New England Kitchen also applied the principles of home economics to feed hungry children. With the support of wealthy Bostonians, New England Kitchen operated the first free school lunch program, offering scientifically developed meals that maximized energy, nutrition, and sanitation. Within five years, the program fed 5,000 students per day across the city and by 1918, similar school lunch programs had emerged in 86 American cities.

Levine, Susan. “School Lunch Politics: The Surprising History of America’s Favorite Welfare Program.” Princeton University Press, 2008: 22.

In 1887, Jane Addams came across a story about a “settlement house” in London — an organization that provided both social services for the poor and opportunities for college-educated women like herself to support working families. She believed such a settlement house could offer a solution to poverty in American cities. With her partner, Ellen Gates Starr, Addams opened Hull House in Chicago in 1889, offering neighborhood residents — most of them immigrants — childcare, health care, and other social services alongside recreation, cultural events, and a safe space to gather and play. Hull House inspired a movement: by 1900, there were at least 100 settlement houses across the U.S.

Fighting Hunger through Education

In addition to providing basic healthcare services, Hull House offered residents of the west side of Chicago English-language lessons, citizenship classes, and educational lectures. These offerings included classes in home economics such as cooking, hygiene, and household management, emphasizing mothers’ responsibilities to ensure that their families ate nutritious meals. The mostly middle-class, college-educated white women who worked at Hull House believed that if poor mothers learned to “properly” manage their households and family diets, they could feed their families healthier meals for less.

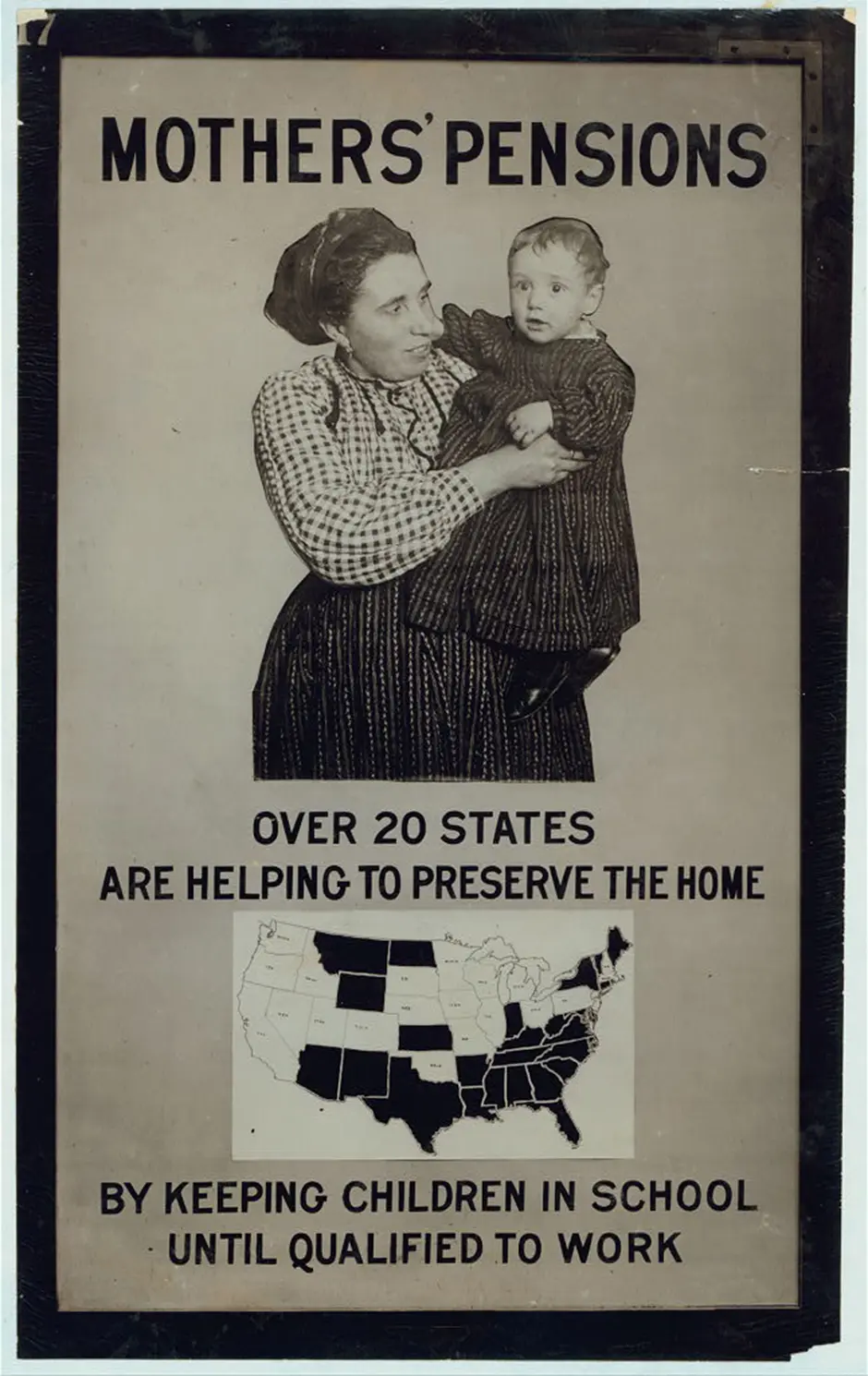

Mothers Pensions

Even before they could vote, women advocated for reforms to improve the lives of mothers and children. Many marshaled support for “mothers’ pensions” to provide state assistance for widows and single mothers so that neither they, nor their children, would be forced to work. These campaigns challenged claims that the desperate circumstances of single mothers could be attributed to character defects or personal irresponsibility. By 1915, seventeen states had introduced some form of assistance for widows and other mothers in need. However, mothers’ pensions were often not available to women of color: in states where they were available, an estimated 96% of families receiving benefits were white.

Minoff, Elsa. “The Racist Roots of Work Requirements,” Center for the Study of Social Policy (Feb. 2020), p. 12. See also Linda Gordon, Pitied but Not Entitled: Single Mothers and the History of Welfare, 1890-1935. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

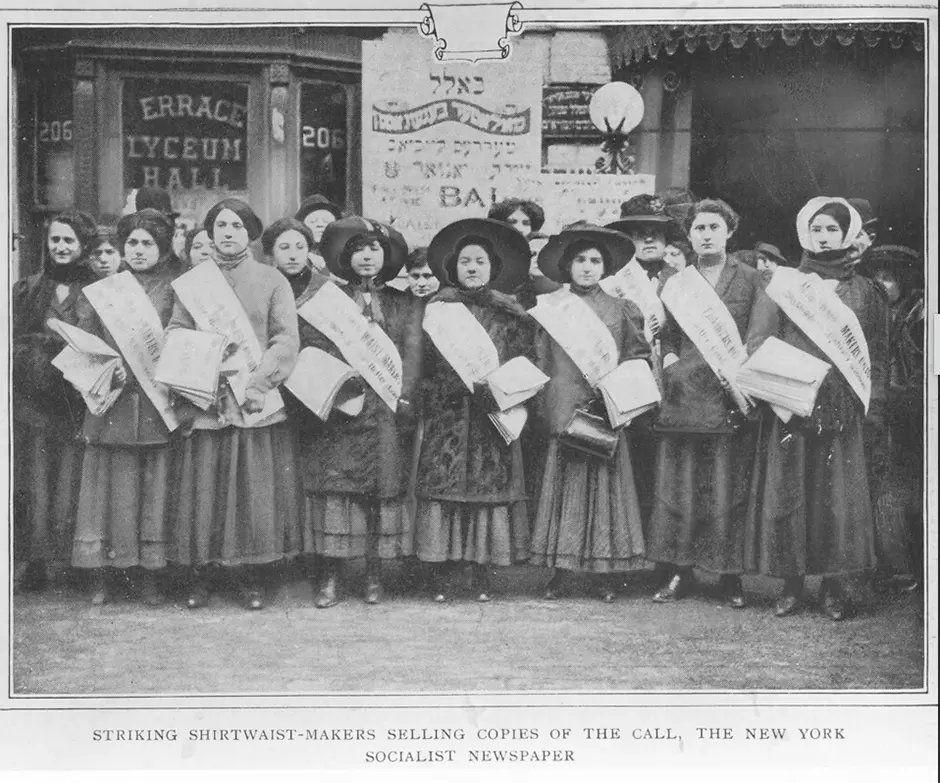

Bread and Roses

Working women pursued their own solutions to hunger and poverty by fighting for improved wages and working conditions. Women faced discrimination from their bosses and from their male trade union leaders, who viewed them as “unskilled” workers more interested in marriage than their careers. In November 1909, women garment workers defied these expectations. Some 20,000 women took on New York City’s shirtwaist makers, walking off the job and enduring harassment and hundreds of arrests for eleven weeks through the winter. The “Uprising of the 20,000” inspired union organizing among women across the country that increased wages for thousands.

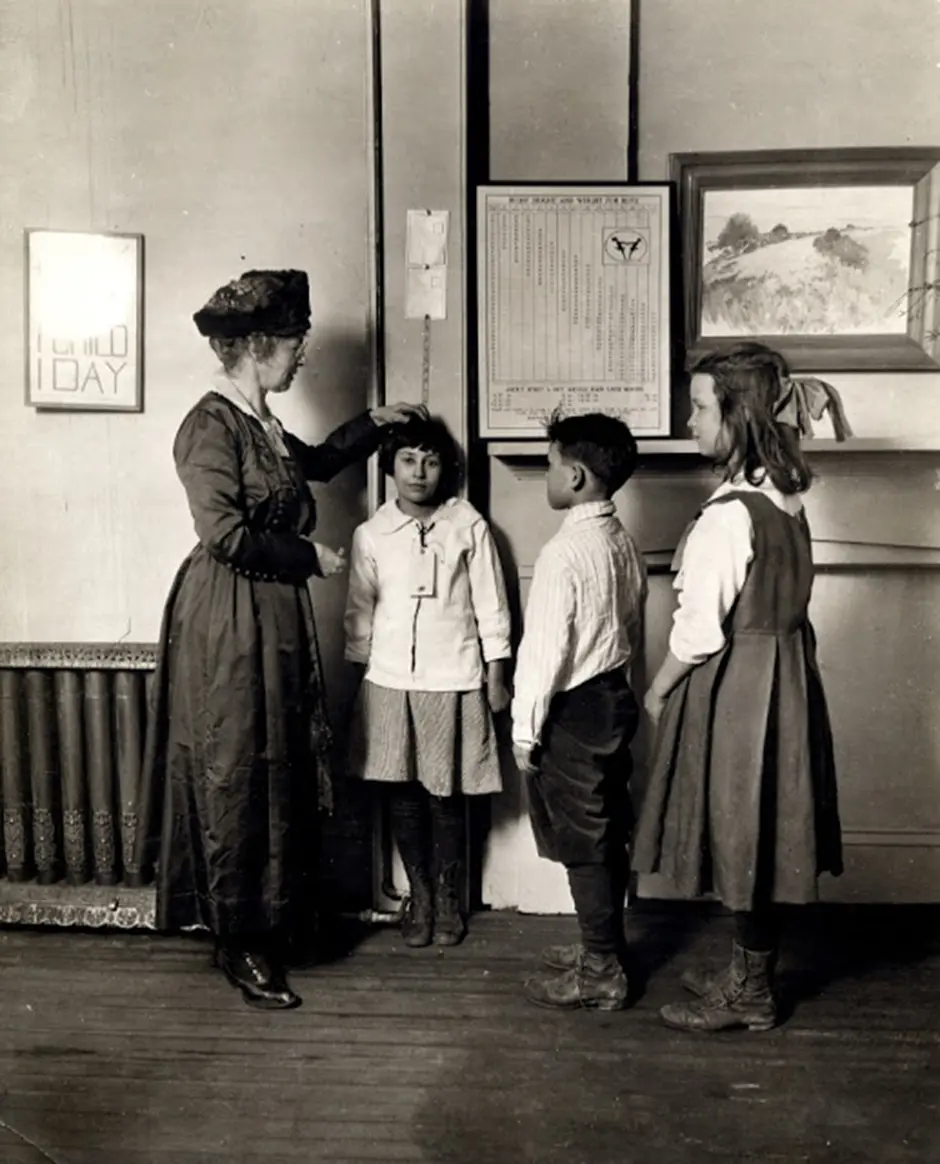

The Dark Side of Nutrition Science

Some Americans distorted insights from nutrition science to spread pseudo-scientific arguments about white racial superiority. Proponents of “racial science” claimed that the endemic poverty of immigrant neighborhoods was a byproduct of biological differences and inherited racial traits. Racist arguments about the “fitness” of poor immigrant mothers cited new national height and weight standards, originally developed to measure malnutrition in children. The most extreme positions blended theories of biological racial hierarchy with Charles Darwin’s concept of natural selection to justify policies that would ensure racial purity, such as segregation, sterilizations, and immigration restrictions.

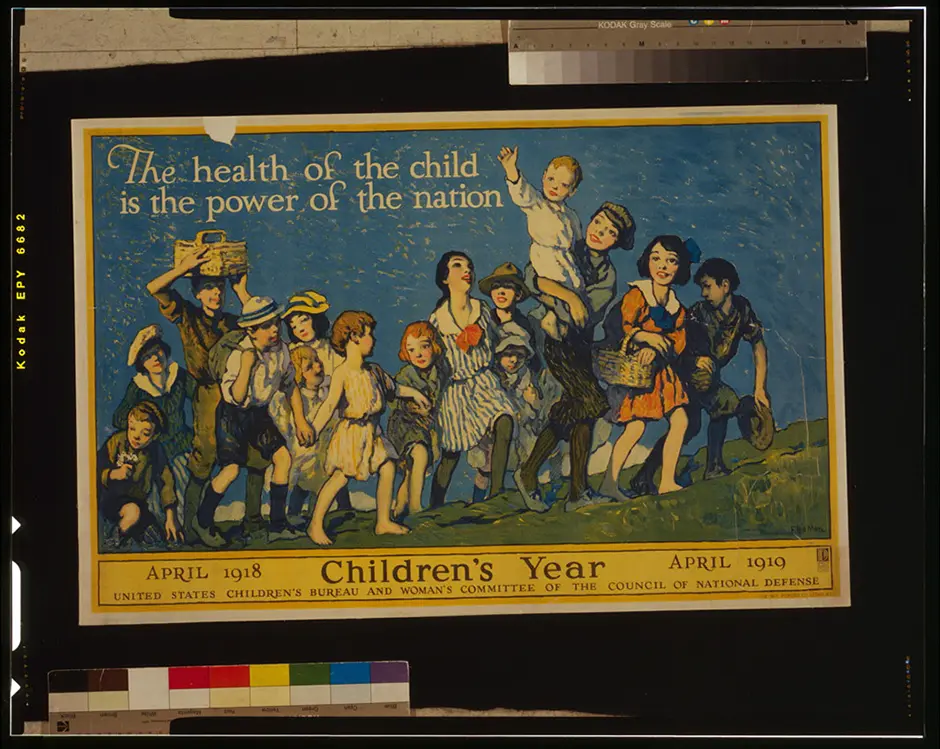

Children's Bureau

After years of advocacy by women reformers, in 1909, President Theodore Roosevelt convened a White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children, resulting in a new agency: a Children’s Bureau. President Taft signed legislation creating the Children’s Bureau in 1912, appointing social worker Julia Lathrop, a veteran of Hull House, as its first Chief. The early Children’s Bureau was primarily charged with investigation and reporting on the welfare of children. Only through the passage of legislation in subsequent years did the Children’s Bureau gain the power to enforce new laws and enact new assistance programs as originally imagined.

Legacies of Hull House

Hundreds of residents and volunteers contributed to Hull House over more than a century in operation. College-educated women like Jane Addams applied their education in innovative ways to meet the needs of the community. They were activists, suffragists, and social reformers. Together, these women were one of the most important organizing networks of the Progressive Era, when reform-minded activists applied scientific methodologies for the benefit of society. These women made significant contributions to social science, and many alumnae became leaders of the agencies they fought to establish, such as Julia Lathrop, the first director of the Children’s Bureau.

The Sheppard-Towner Act, 1921

The enfranchisement of women elevated “women’s issues” in politics immediately. The first major piece of legislation passed in the wake of women’s suffrage was the Promotion of the Welfare and Hygiene of Maternity and Infancy Act (the Sheppard-Towner Act), providing new forms of health care for mothers and their children. Proposed by Representative Jeanette Rankin, the first woman elected to Congress, the legislation provided federal funding for maternity care, expanded funding for health education, and provided for translation of nutrition information into several languages. While Congress did not renew its funding after 1929, many of its programs were eventually codified in the Social Security Act of 1935.

Fighting Hunger in the Domestic Sphere

Rapid industrialization in the nineteenth century gave rise to a growing number of middle-class families who did not depend on their daughters to work on family farms or in the home. As a result, an increasing number of women, most of them white, began attending college.

Within universities, women pioneered new scientific research about nutrition and sanitation, advancing a new discipline that came to be known as “domestic engineering” or “home economics.” Some put their education to use to solve hunger in working-class, immigrant neighborhoods, applying social scientific methods to their charity, efforts that gave rise to the settlement house movement.

These were the first attempts to address poverty and hunger comprehensively. But the efforts were premised on the assumption that hunger reflected a lack of education and improper household management by poor, immigrant mothers. Many “domestic scientists” believed that hunger and poverty could be best addressed by changing the behavior of immigrants to better reflect the norms of white, middle-class Americans like themselves.

Some middle- and upper-class women began attending college and started applying their new knowledge to fight against hunger and improve the lives of the immigrant poor.

Museum Map

WISHING

TREE