The Age of Mass Migration

While the dispossession of Native peoples began well before the founding of the United States, the federal government formalized and accelerated the forced removal of Indigenous people from their ancestral lands in the nineteenth century. That displacement — often the result of armed conflict or coerced treaties — enabled the United States’ conquest of vast acres of Tribal territory. The expansion was guided by the idea of “Manifest Destiny” — the belief that the United States’ territorial expansion westward was both inevitable and morally justifiable because white American settlers had a providential mission to control and transform the continent.

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 accelerated western settlement in new ways, enabling the incorporation of new territories into the national market economy. Waves of recently-arrived immigrants moved west and corporations soon followed, seizing opportunities the railroads created. In 1893, historian Frederick Jackson Turner, in his famous address to the American Historical Association, proclaimed that the frontier had closed.

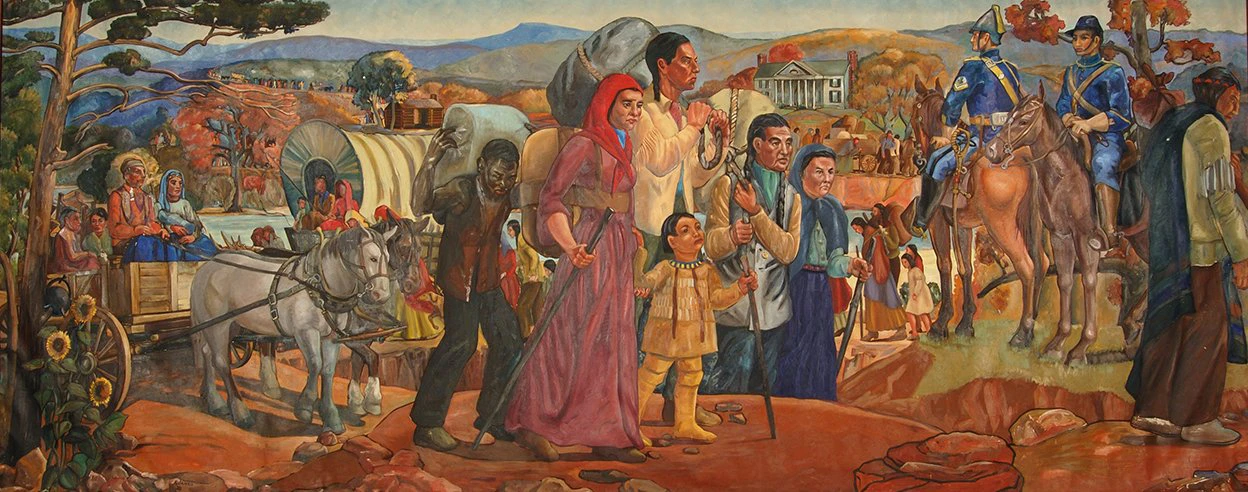

Indigenous dispossession

and displacement

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 authorized the president to negotiate (and/or coerce) treaties that forcibly transferred Cherokee, Muskogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations to territories west of the Mississippi River, known as reservations. Resistance efforts failed, resulting in the “Trail of Tears” in 1838, during which thousands of Cherokees died. Many other tribes faced similar displacements and loss of life.

In 1887, the Dawes General Allotment Act upended centuries-old Indigenous systems of communal land stewardship by opening 100 million acres of “surplus” lands to private sale. These policies disrupted Indigenous communities’ relationship to traditional food sources, replacing fishing, hunting, and gathering with distributions of food rations that forced reliance on government-provided food.

European imperial trade incursions into Asian markets disrupted ways of life in southern coastal China as well as Korea, Japan, India, and the Philippines, pushing migrants to consider crossing the Pacific for better opportunities in the U.S. Some emigrated to Hawai’i to work on American-owned plantations; others traveled farther to California. Chinese contract workers — sometimes referred to derisively as “coolies” — soon became a preferred source of cheap labor for mines, railroads, and plantations throughout the U.S.

The wave of Chinese immigration sparked a violent, nativist backlash. Calling Chinese immigrants “undesirable aliens,” a campaign to bar their entry to the U.S resulted in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first federal immigration restriction explicitly based on race and/or national origins. By 1924 any immigrants from the “Asiatic Barred Zone” were prohibited entry.

Virulent racism made life for Asian immigrants particularly difficult, denying them access to most housing and job opportunities. Nonetheless, Asian immigrants worked together to preserve their cultures and traditional foods, which ultimately became integral parts of the American diet.

Profound economic, social, and cultural transformations of the nineteenth century destabilized empires throughout Europe, giving rise to revolutions from which several new nation-states emerged. In combination with industrialization, the instability put thousands of people across the continent on the move, particularly those from rural areas in Southern and Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and the Eastern Mediterranean. Over 20 million European immigrants arrived to the East Coast between the end of the Civil War and 1924, seeking refuge and opportunities to rebuild their lives in the U.S.

European immigrants struggled to find housing and good-paying jobs, most settling in densely crowded, racially segregated urban neighborhoods. While some Americans worked to feed impoverished immigrants, many others relied on pseudo-scientific arguments about racial purity to argue that hunger in immigrant neighborhoods proved the new arrivals were “unfit” for citizenship. Fears that the number of immigrants threatened to overwhelm the capacity of the U.S. to feed its citizens resulted in the 1924 National Origins Act, which imposed strict quotas that sharply curtailed immigration from Europe and effectively banned immigration from Asia.

“Street Arabs in Sleeping Quarters,” Jacob A. Riis Museum of the City of New York.

Nearly one third of the Ashkenazi Jewish population from “the Pale of Settlement,” an area encompassing parts of present-day Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Latvia, and Lithuania, fled Eastern Europe before the outbreak of the first World War, after nearly a century of segregation and forced assimilation. The assassination of the Russian Tsar in 1881 unleashed a wave of violent attacks, known as pogroms, on the region’s Jewish communities, prompting many to flee. Colored by antisemitism and xenophobia, hunger among Jewish migrants in the U.S. was often dismissed as a byproduct of their “backwards” traditions or a reflection of their racial inferiority.

While the National Origins Act of 1924 imposed limits on immigration from much of the world, countries in the Western Hemisphere were exempt. American farmers and business owners who relied on migratory labor from neighboring Mexico lobbied to keep America’s southern border “open.” Workers regularly crossed in and out of the U.S. through its southern border at will. The Mexican Revolution prompted some migrants to settle more permanently in the U.S., and politicians from border states — particularly California — made unsuccessful attempts to include Mexico in the National Origins quotas.

The National Origins Act did attempt to restrict border crossings from Mexico in another way: it authorized the creation of the U.S. Border Patrol. Recruited from existing law enforcement agencies, including the Texas Rangers, sheriffs’ departments, and customs inspectors, Border Patrol agents were armed officers tasked with “securing” the nation’s borders. The bulk of their enforcement power was directed at the southern border and often came with mistreatment, brutality, and humiliation, much of which has been directed towards migrants from Mexico ever since.

In 1876, Congressional Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the former Confederacy. Southern states immediately stripped rights from Freedmen and formerly-enslaved citizens, recodifying white supremacy into law. Coupled with an ongoing campaign of racial violence, this institutionalized white supremacy and racial inequality became a system known as “Jim Crow.”

The deep injustices of Jim Crow, combined with an increasing availability of industrial jobs, induced millions of Black families to leave the South and seek freedom and prosperity elsewhere. “The Great Migration” brought some 1.6 million Black migrants to cities in the North and West between the 1910’s and 1930’s.

Even after migrating, Black families still confronted persistent racial discrimination, were denied access to housing and well-paying jobs, and were subjected to hostility and reactionary racial violence, demonstrating that the inequities of Jim Crow were by no means limited to the South. Despite these obstacles, Black migrants created new forms of culture, self-reliance, and community that forever changed their new homes and the United States as a whole. Jacob Lawrence — one of the most prolific visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance — painted a series of sixty paintings depicting the mass relocation of southern Black migrants to cities.

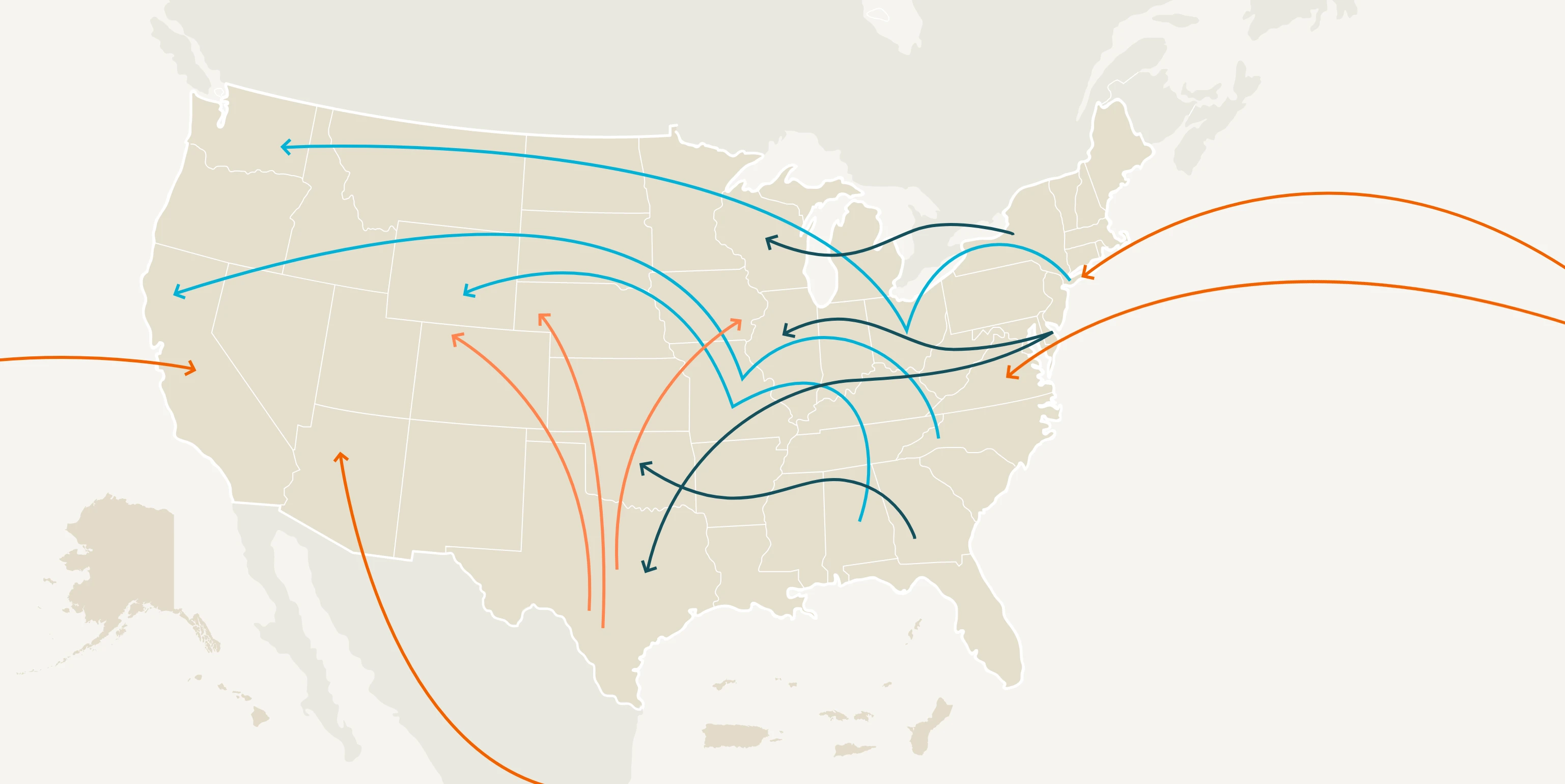

In the nineteenth century, a variety of global developments converged, sending millions of people on the move. The Industrial Revolution transformed economies across the world. That industrialization unleashed widespread social and political unrest and upheaval. Around the world, centuries-old dynasties faced revolution and sustained movements for emancipation and democratic reform. At the same time, European empires expanded their colonial realms, incorporating more territories into systems of extraction, plunder, and subjugation.

Many of those displaced by this widespread instability left their homes, ushering in a period of mass migration, during which about 24 million people migrated to the United States. This fundamentally reshaped how Americans understood hunger and poverty. Poverty became more widespread and more visible than ever before. Hungry migrants, particularly children, became symbols of the inequalities of the age and catalysts of debates about how (or whether) to address those inequalities.

This exhibit shows the different migration streams that occurred in the nineteenth century, when some 24 million people migrated to the United States and reshaped how Americans understood hunger and poverty.

Museum Map

WISHING

TREE