Hunger and the

Culture Wars

The Welfare Queen

Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign centered the story of Linda Taylor, branded by newspapers as a “welfare queen.” There was nothing typical about Taylor or her actions, but her case became an invidious stereotype — the scheming, minority welfare swindler, living high off the government dime and honest American taxpayers. Readers were led to think of her in racialized and criminalized terms as a Black woman. This sexist and racist term became a popular trope, which is still used in derogatory ways by lawmakers attempting to dismantle or de-fund the safety net.

Josh Levin, The Queen: The Forgotten Life Behind an American Myth (Thorndike Press, 2019).

Food Stamp “Fraud”

Reagan invoked the “welfare queen” alongside another, equally racist trope of the “strapping young buck” — a Black man using food stamps to buy T-bone steaks while thrifty Americans made do with hamburgers. Reagan’s message was clear: undeserving Black people were cheating the food stamp program, wasting benefits paid for by working white taxpayers. Reagan’s claims about fraud stirred up a media frenzy, with stories that persistently misrepresented the food stamp program, overstated the generosity of the benefits people received, and failed to mention that such cases were just a small fraction of the 22 million families enrolled in the program.

“Definitely not USDA Approved,” Time Magazine. Aug. 23, 1982.

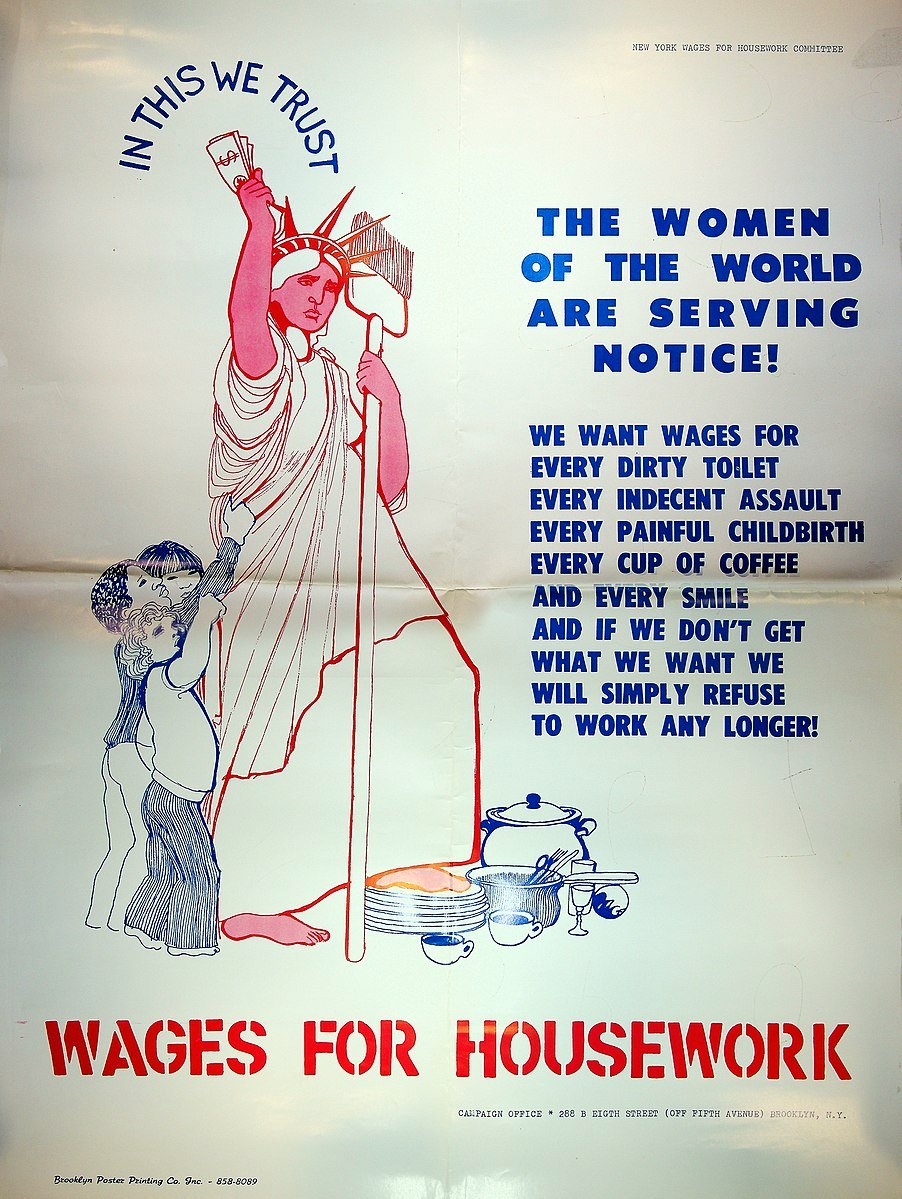

Women for Wages for Housework

As women began to enter the paid workforce in higher numbers, the backlash was clear and persistent. Middle-class working women were deemed selfish for not staying home with their children, but stay-at-home moms who needed assistance were labeled as lazy tax burdens. Beginning in the 1970’s, the Women for Wages for Housework movement emerged, arguing that the unpaid labor of maintaining a home and raising children was work that deserved state compensation. The movement gained traction during the “Reagan Revolution,” as it showed how transformative justly compensating women for housework could be.

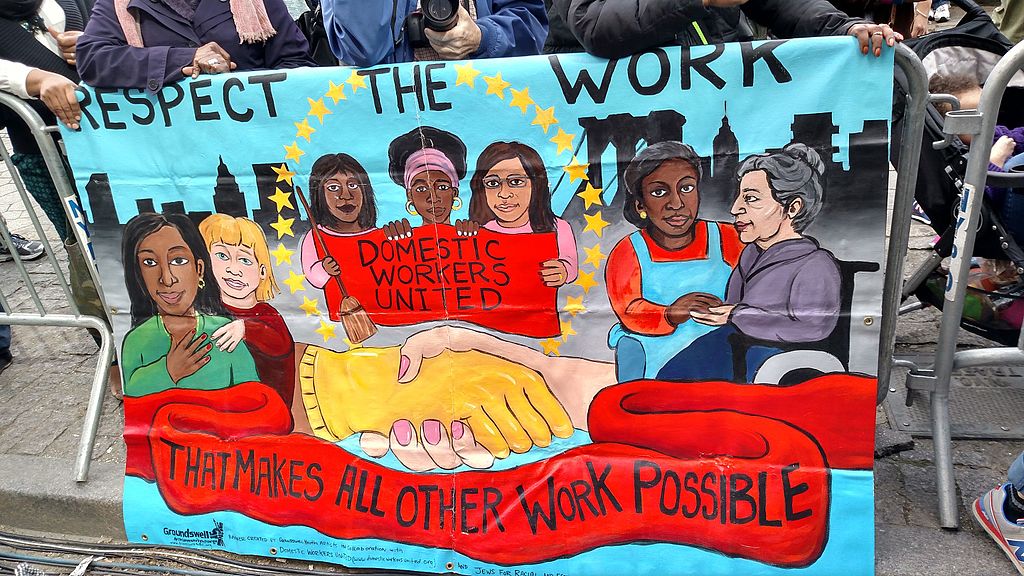

Domestic Workers Organize

For centuries, women filled domestic roles without or with deeply undervalued pay. Racialized legacies of enslavement and servitude reinforced the subordination of women of color who worked as domestics. Domestic workers were excluded from the Social Security Act and many of the workplace protections of the New Deal, and because many were immigrant women, domestics were particularly vulnerable to human trafficking and various forms of imprisonment.

In the 1980’s and 1990’s, advocates demanded that female-dominated jobs be paid at a rate comparable to male-dominated jobs of similar skill and education. Immigrant domestic workers started organizing to defend against wage theft and abuse, forming new organizations to take collective action.

Boris, Eileen and Premilla Nadasen, “Domestic Workers Organize!,” WORKING USA: The Journal of Labor and Society vol. 11 (Dec. 2008): 413-437.

Return of the Welfare Queen

By 1996, revival of the “welfare queen” myth by both media and political leaders — led in Congress by Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich — succeeded in urging President Clinton to sign into law the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, commonly known as welfare reform. This legislation included block grants to states that set their own eligibility standards, time limits, and work requirements for social safety net programs. Racist and sexist portrayals of welfare recipients by the media and policymakers painted these “reforms” as necessary to prevent willful idleness and criminal behavior among struggling Americans, though little evidence of widespread fraud existed.

Culture Wars

President Ronald Reagan’s election marked the triumph of a conservative political order grounded in promises to cut taxes, eliminate waste, and lower spending. He centered individual personal responsibility over community responsibility, vilifying women and people of color as victims of their own poor behavior who were damaging the broader American public. President Reagan used his skill for storytelling to promote an aggressive policy agenda of austerity, highlighting a single welfare fraud case to build the support needed to cut a million hungry Americans off from receiving food stamps.

Cultural touch points like music, TV shows, and global media events also reframed hunger as an individual problem. Business leaders used cultural dog whistles to present ending hunger as a corporate and charitable responsibility, reducing corporate tax burdens in turn. Corporate giving power led to the growth of new food charities, which collaborated with celebrities to promote their causes. By the mid-1990s, the culture wars had engendered a new popular consensus: that widespread hunger was a problem exclusive to the third world, and that any domestic hunger was a byproduct of individual failures.

The culture wars of the 1980’s and 1990’s reshaped popular perceptions of food and hunger in negative and fundamental ways, influencing both political will and government policies in turn.

Museum Map

WISHING

TREE