The stock market collapse in 1929 initiated a cascade of economic effects that devastated American businesses. Millions of Americans lost their jobs, with the unemployment rate reaching as high as 25%, and even those lucky enough to keep their jobs saw their wages and incomes decline by 40%. The result was unprecedented levels of hunger, and the scale of need quickly overwhelmed charities. Images of blocks-long breadlines in cities across the country made hunger visible in ways it had never been before, convincing many Americans that government intervention was needed.

Statistics from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

“The Test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.” – Franklin Delano Roosevelt

The shocking image of the breadline endures in the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington, DC. The outdoor installation features sculptures of five men waiting in a breadline, alongside a farmer and his wife – symbols for the crisis of the Depression.

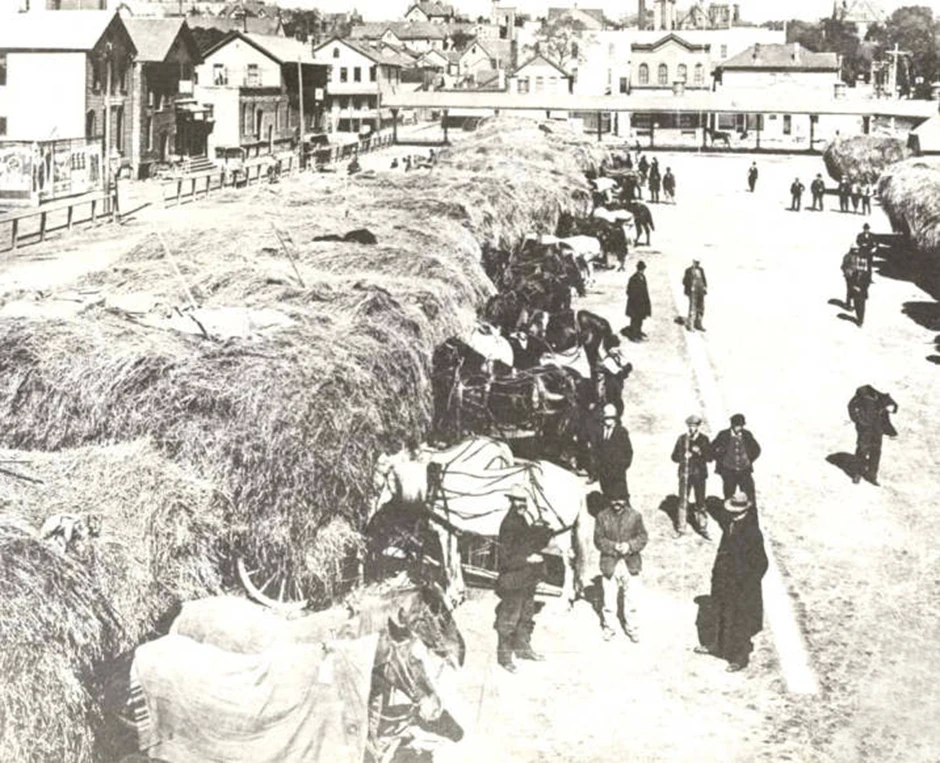

Breadlines Knee Deep in Wheat

When food demand increased worldwide after World War I, American farmers expanded production. But falling incomes and widespread unemployment in the Depression drove down the prices of basic staples — some dropping as much as 50%. Farm families could not sell their crops without incurring massive losses, creating overwhelming surpluses that many farmers chose to destroy or leave to rot in the fields. The combination of overproduction and underconsumption created what Oklahoma-based writer Oscar Ameringer described as a “plague of plenty,” leading to a rapid uptick in rural poverty.

Poppendieck, Janet. Breadlines Knee Deep in Wheat: Food Assistance in the Great Depression. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014.

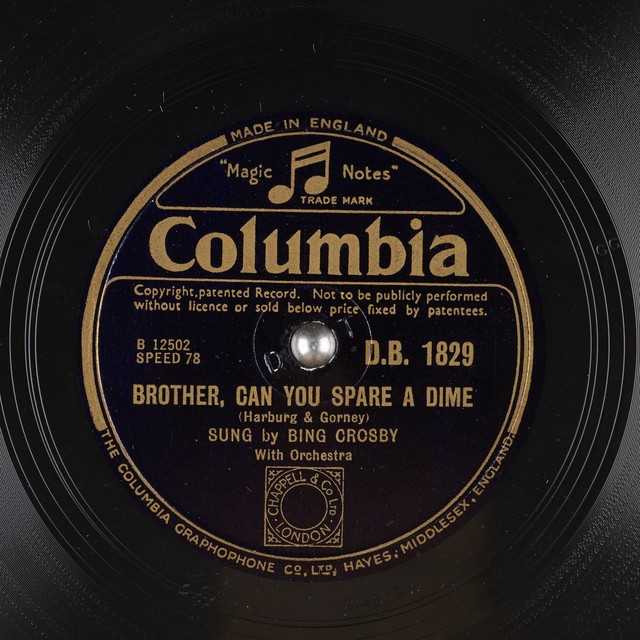

Brother, Can You

Spare a Dime?

“Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” gave voice to the millions of Americans struggling to get by during the Depression. Composer Jay Gorney, who immigrated from Białystok (modern-day Poland), based the song on a Russian-Jewish lullaby; lyricist E. Y. Harburg added refrains he heard on street corners to authentically reflect the experiences of unemployed people. “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” captured the grief, frustration, and anger of so many people who felt abandoned by their country.

The Great Depression in America: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Vol. 1 ed. William H. Young and Nancy K. Young – p. 72-73.

Impacts of the Dust Bowl

Already stressed by collapsing food prices, farm families in the Great Plains endured a series of dust storms that severely damaged the ecology and agriculture of the prairies. The Dust Bowl was caused by a combination of severe drought, an insufficient understanding of the ecosystem, and a refusal to apply Indigenous agricultural methods and dryland farming techniques that would prevent topsoil erosion. It resulted in the displacement of thousands of farm families — many of whom headed west to California and other coastal states.

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum.

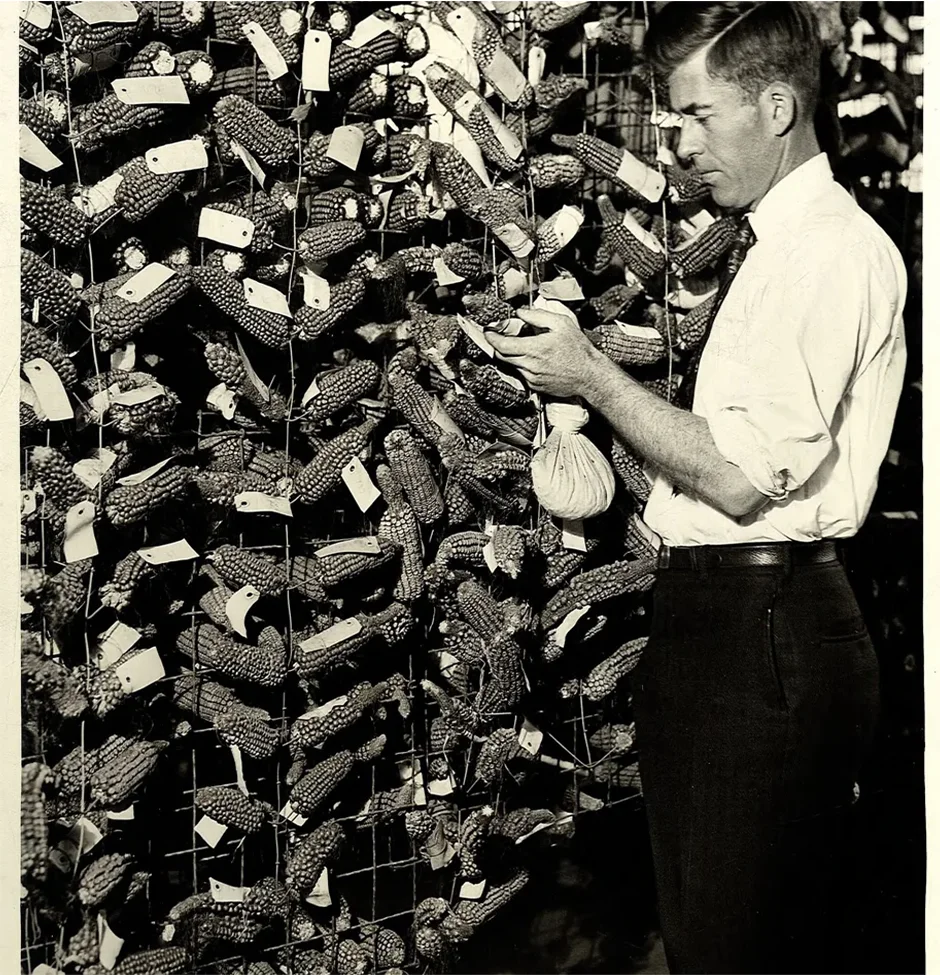

A New Deal for Farmers

Raised on a corn farm in Iowa, Henry Wallace became a champion of land-owning farmers as Secretary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), introducing an array of programs and protections for rural communities. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 created price controls for staple commodities and empowered USDA to purchase surplus goods, which were distributed to welfare offices and local schools. This became the first federal food assistance in this country and the seed of the Food Stamp Program, helping to feed hundreds of thousands of hungry Americans.

While designed to help struggling farm families, the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) deepened the crisis faced by “tenant farmers” who farmed on rented land. To eliminate surplus and stabilize prices, the AAA included incentives for landowners to reduce production by culling their herds and leaving their fields fallow. In the South, where tenancy and sharecropping had prevailed since Reconstruction, landowners opted to evict families growing crops on their land. Thousands of farm families, Black and white, were pushed off land they had called home for generations, joining the stream of displaced migrants moving west.

Recognizing the scale of the displacement, the U.S. Department of Agriculture attempted to provide emergency housing for white displaced tenant farmers through initiatives like the Subsistence Homestead Program and, later, the Resettlement Administration. The government excluded Black farmers and others from these planned agricultural communities, leaving them with nowhere to go and seeding generational poverty.

“We Will Work Again” (1937)

“[We] were the first to lose our jobs when Old Man Depression came along and the last to get them back. […] One out of every four of us was on relief. […] Without jobs, we had no money. Without money, we could not purchase food for the hungry mouths at home. Our only hope lay in charity. Hunger drove our people to the breadlines. […] Then came the federal government’s work program. One by one it took us out of the breadline. It gave us a new chance to take a normal place in the life of our community. […] Now we work again!”

The Works Progress Administration funded an array of programs for unemployed Americans, as well as cultural programs that employed thousands of struggling writers, artists, and performers. The agency provided 8.5 million total jobs before it was shut down in 1943.

A Good Lunch

In addition to jobs programs, public works projects, and cultural promotion, the U.S. government’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) offered first-of-their-kind grants and support for local school lunch programs. The WPA piloted “school lunch units,” offering funding to school districts to hire bakers, cooks, and “lunch ladies” to staff and/or expand on-site cafeterias. Before it ended in 1943, the WPA’s school lunch program employed 5,000 people to operate kitchens and cafeterias in 35,000 schools nationwide, feeding 350,000 kids per day.

Susan Levine, School Lunch Politics: The Surprising History of America’s Favorite Welfare Program (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008): 44.

A New Deal for Indian Country

In the 1930’s, President Roosevelt initiated an array of programs known as the “Indian New Deal,” aiming to restore Tribal self-governance and autonomy. But the administration continued its paternalistic policies and rejected Indigenous knowledge and needs, aiming to “modernize” agricultural practices on reservations in the wake of the Dust Bowl.

Rather than expanding tribes’ access to the ancestral waterways and pasture lands that could sustain their animals, the Churro sheep — integral to Diné, Hopi, and Apache food and culture — were decimated by mandates that Tribes cull herds. Only decades later was the Churro population restored enough to no longer be endangered; the communal work of reintegrating these essential foodways continues.

An Unequal Recovery

In order to pass his expansive agenda, President Roosevelt brought together a fragile coalition that included midwestern farmers, northern businessmen, racist white southerners, and urban working-class voters. As a result, many New Deal programs had exemptions and compromises built in, including explicit exclusions of Black, Indigenous, and other people of color. While the New Deal brought relief and stability to many white Americans, including once-excluded European immigrants and their descendants, economic recovery remained illusory for people of color. Photographer Margaret Bourke-White captured these contradictions in her 1937 photo of Black flood victims in Louisville seeking emergency food aid.

Hungry Americans

When the stock market crashed in 1929, desperate farmers destroyed crops in an effort to stabilize prices. Then, a wave of massive dust storms swept across the plains, displacing thousands of farm families. Many of these families sought refuge in the west, further devastating the American food supply.

The New Deal launched several programs using the federal government’s power to stabilize the food supply and directly impoverished people, including a new pilot program known as “Food Stamps.” Passage of the New Deal, however, required President Roosevelt to make significant compromises, including systematic exclusions of Black, Indigenous, and other Americans of color. The economic relief and recovery promised by the New Deal remained out of reach for communities of color for many years to come.

Citation:

Levine, Susan. School Lunch Politics: The Surprising History of America’s Favorite Welfare Program. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008: 44.

This exhibit shows the breadth of New Deal programs, which marked the first federal efforts to address hunger in America.

Museum Map

WISHING

TREE