Norman Rockwell,

“Freedom From Want”

President Franklin D. Roosevelt imagined a world founded upon Four Freedoms — “freedom from want,” “freedom from fear,” “freedom of speech,” and “freedom of worship.” Artist Norman Rockwell painted a series of paintings visualizing these four freedoms, each paired with short essays. Rockwell’s painting evoked a traditional, all-white cast sitting down to an idealized American holiday meal. But the accompanying essay was written by a Filipino American, Carlos Bulosan, detailing the experiences of the migrant farm workers of color who kept dining tables like this one full.

Carlos Bulosan, “Freedom From Want”

When Norman Rockwell’s famous painting ran in The Saturday Evening Post, it was accompanied by an essay written by Carlos Bulosan, a Filipino American migrant worker. His essay about labor, farm life, and hunger offers a stunning juxtaposition against Rockwell’s imagining of a white, middle-class family’s holiday feast.

We have been marching for the last 150 years. We sacrifice our individual liberties, and sometimes we fail and suffer. Sometimes we divide into separate groups and our methods conflict, though we all aim at one common goal. The significant thing is that we march on without turning back. What we want is peace, not violence. We know that we thrive and prosper only in peace.

We are bleeding where clubs are smashing heads, where bayonets are gleaming. We are fighting where the bullet is crashing upon armorless citizens, where the tear gas is choking unprotected children. Under the lynch trees, amidst hysterical mobs. Where the prisoner is beaten to confess a crime he did not commit. Where the honest man is hanged because he told the truth.

We are the sufferers who suffer for natural love of man for another man, who commemorate the humanities of every man. We are the creators of abundance.

We are the desires of anonymous men. We are the subways of suffering, the well of dignities. We are the living testament of a flowering race.

But our march to freedom is not complete unless want is annihilated. The America we hope to see is not merely a physical but also a spiritual and an intellectual world. We are the mirror of what America is. If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.

What do we want? We want complete security and peace. We want to share the promises and fruits of American life. We want to be free from fear and hunger.

— Carlos Bulosan, Filipino American migrant worker, 1943

Ration D, pictured in Life magazine

During World War II, food scientists from companies like Kellogg’s and Hershey created new products that stored easily and did not spoil in various climates. Wherever they were deployed in the world, troops were supplied with a common set of innovative rations. One was Ration D, a densely caloric “energy bar” made of oats and chocolate, intentionally designed by Hershey to taste bad so that troops would save them for emergencies. After the war ended, innovations in food processing, packaging, and the use of preservatives carried over into everyday products.

Japanese American Children

at Minidoka Camp in Idaho

120,000 Japanese Americans spent the war years as hostages, forcibly relocated to so-called “internment camps” by a xenophobic and unconstitutional federal policy after the attack on Pearl Harbor. “Evacuees” were unable to work or to grow their own food, so they ate according to the dictates of the federal government — meager and culturally unfamiliar mainstays of the Standard American Diet. A few Issei (first generation Japanese immigrants) staged hunger strikes, but for the most part, experiences in the camps accelerated trends of culinary assimilation for Nisei (Japanese Americans born in the U.S.).

Weenie Royale: Food and the

Japanese Internment

Listen to Japanese Americans share stories of how internment shaped their family foodways in this NPR segment by the Kitchen Sisters.

“New Frigidaire Refrigerators!”

by General Motors

Boosted by savings, maturing bonds, and low-interest loans from post-New Deal agencies, thousands of white middle-class families bought new homes in new suburban tracts after the war. Major companies like General Motors helped furnish, while advertisers portrayed this post-war age of mass consumerism. Suburban women received special recognition from the ad men who continually urged them to upgrade their kitchen appliances. With war-tested equipment, any suburban ranch-style house had the technological potential to feed a small army — of children, as it turned out for many.

Betty’s First TV Show

A growing food publishing industry began teaching the average household how to prepare the “Standard American Diet.” In 1954, General Mills sponsored a radio show with the archetypal “Betty Crocker,” performed by Adelaide Hawley, nine times a week. 8.4 million households tuned in to this popular program monthly. After the war, Betty Crocker informed wives that they owed their husbands and children hearty meals and relief from culinary “monotony.” To this day, kitchen duty in the suburban home is gendered, and thus invisible and uncompensated, labor.

Harvey Levenstein, Paradox of Plenty: A Social History of Eating in Modern America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

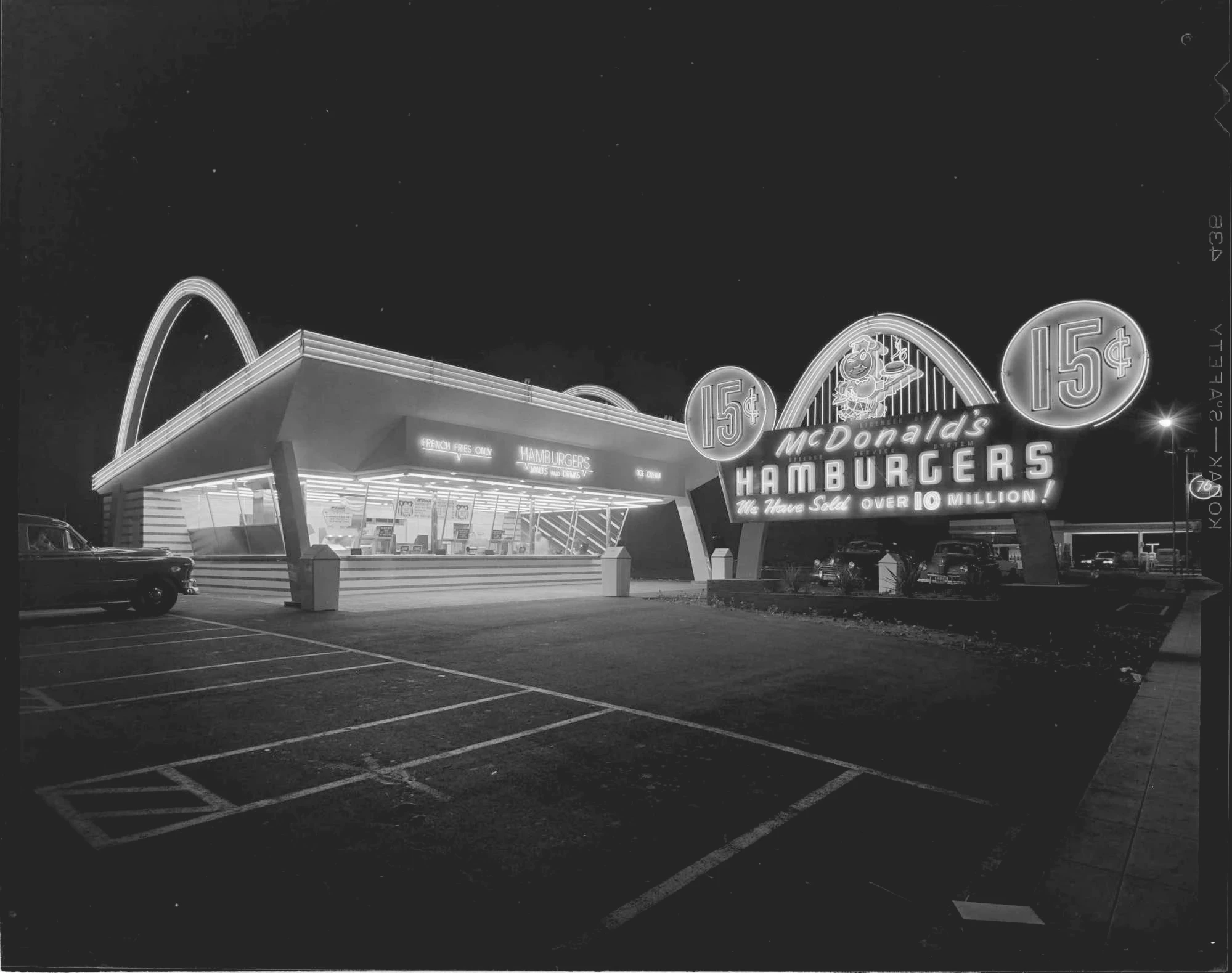

Roadside View of McDonald’s

Simple meals from McDonald’s — the hamburger, milkshake, and fries — were emblematic of widespread adoption of the meat-and-dairy-heavy “Standard American Diet.” The McDonald brothers built the modern drive-in restaurant, having customers stop their cars and give their orders through a kitchen window. This sped up service, but the McDonald brothers wanted even more efficiency. They hired consulting engineers from Environmental-Safety Consultants, a California firm that had invented wartime food distribution techniques, to redesign their kitchens for “quality, service, cleanliness, and value.”

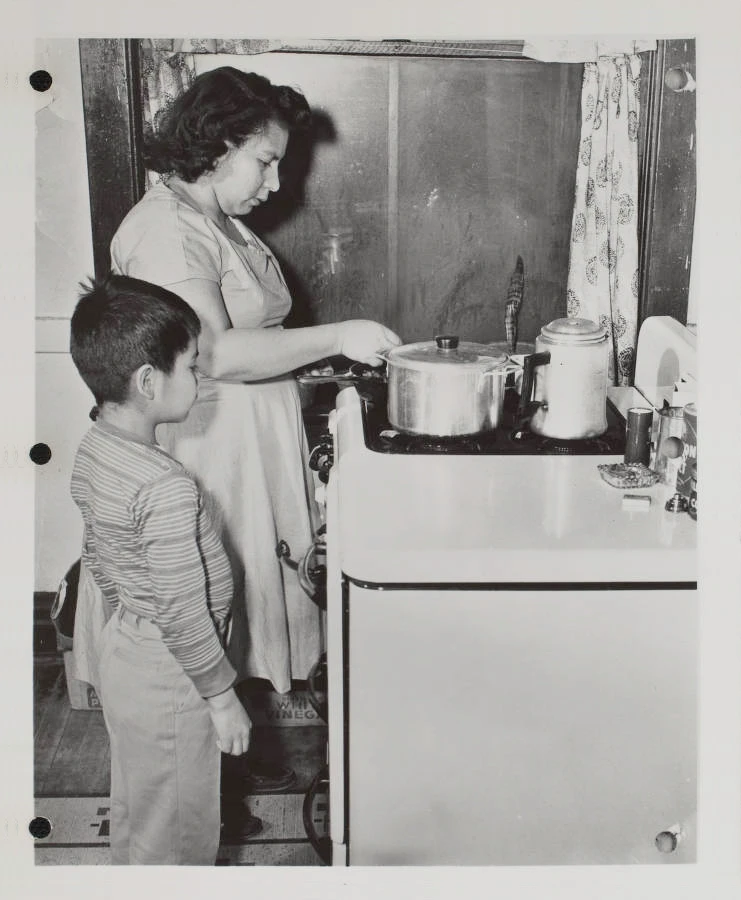

Gonzales family photograph,

Chicago

The 1950’s saw a reversal in policy as Congress sought to end all federal obligations to tribes. Citing widespread poverty and unemployment on reservations, government officials initiated tribal “termination.” Approximately 100 tribes and bands lost federal recognition, and millions of acres of tribal land became available for sale. Government officials distributed “relocation literature” promising one-way transportation to more prosperous lives in cities with industrial jobs, modern homes, and cars. These were empty promises. Like some 750,000 people who migrated to cities through these efforts, Ms. Gonzales and her son, both Arapahos from Santa Fe, “relocated” to the Chicago kitchenette pictured here. Indigenous people struggled to find housing and good jobs, facing worse hunger in cities than before. Government officials would later admit the “relocation” program was “a one-way ticket from rural to urban poverty.“

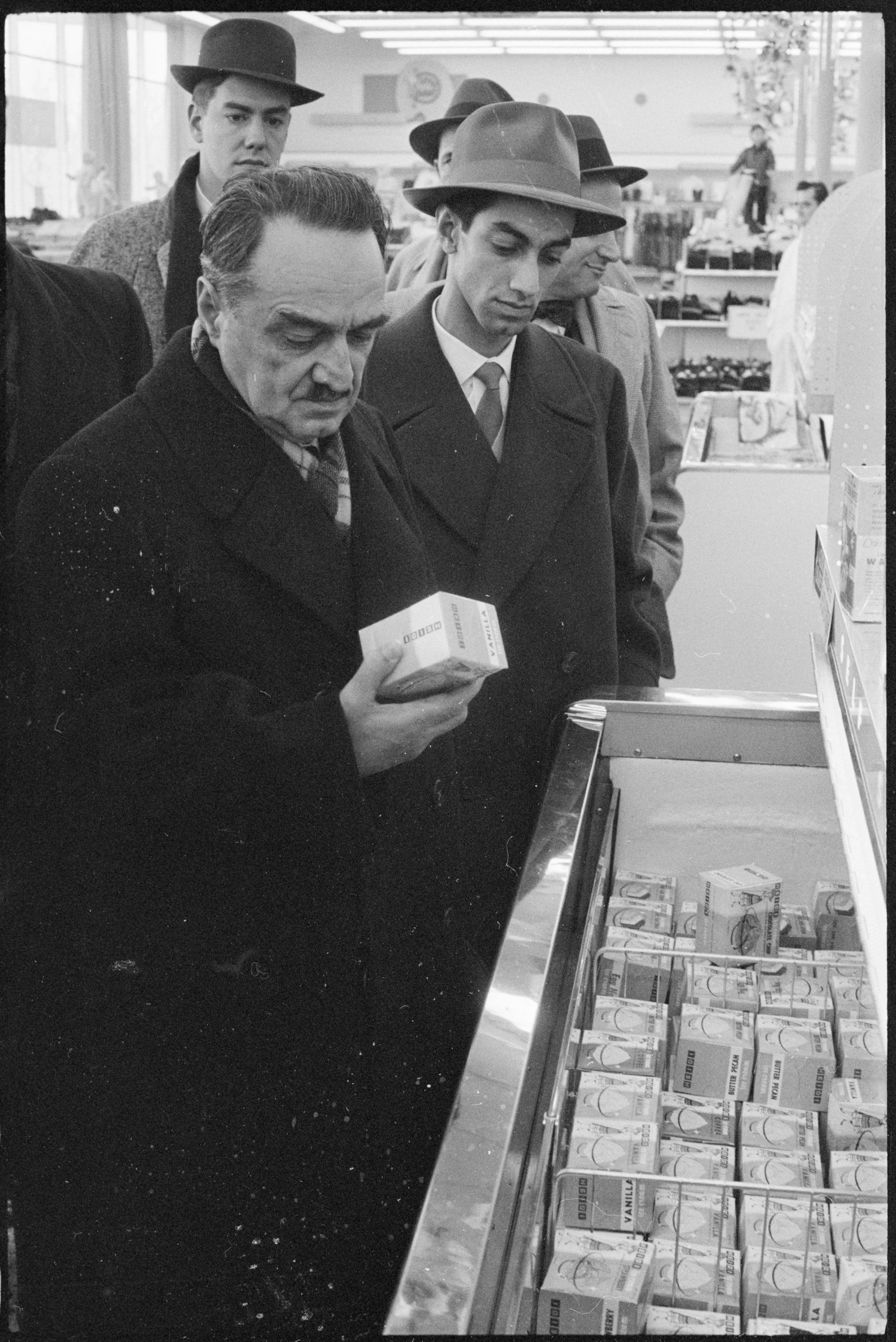

Soviet Officials

and Ice Cream

The highly managed communist food system in Soviet Russia offered a sharply contrasting approach to the American capitalist food system. In January 1959, Soviet official Anastas Mikoyan encountered the U.S. free enterprise food system during an unofficial visit. This picture of Mikoyan visiting a supermarket captured his curiosity at an open cooler filled with boxes of ice cream, signifying the availability of cheap, reliable electricity for refrigeration in stores and homes, the reliance of Americans on dairy as part of the “Standard American Diet,” and an economy thriving on imported sugar from plantations on Caribbean islands.

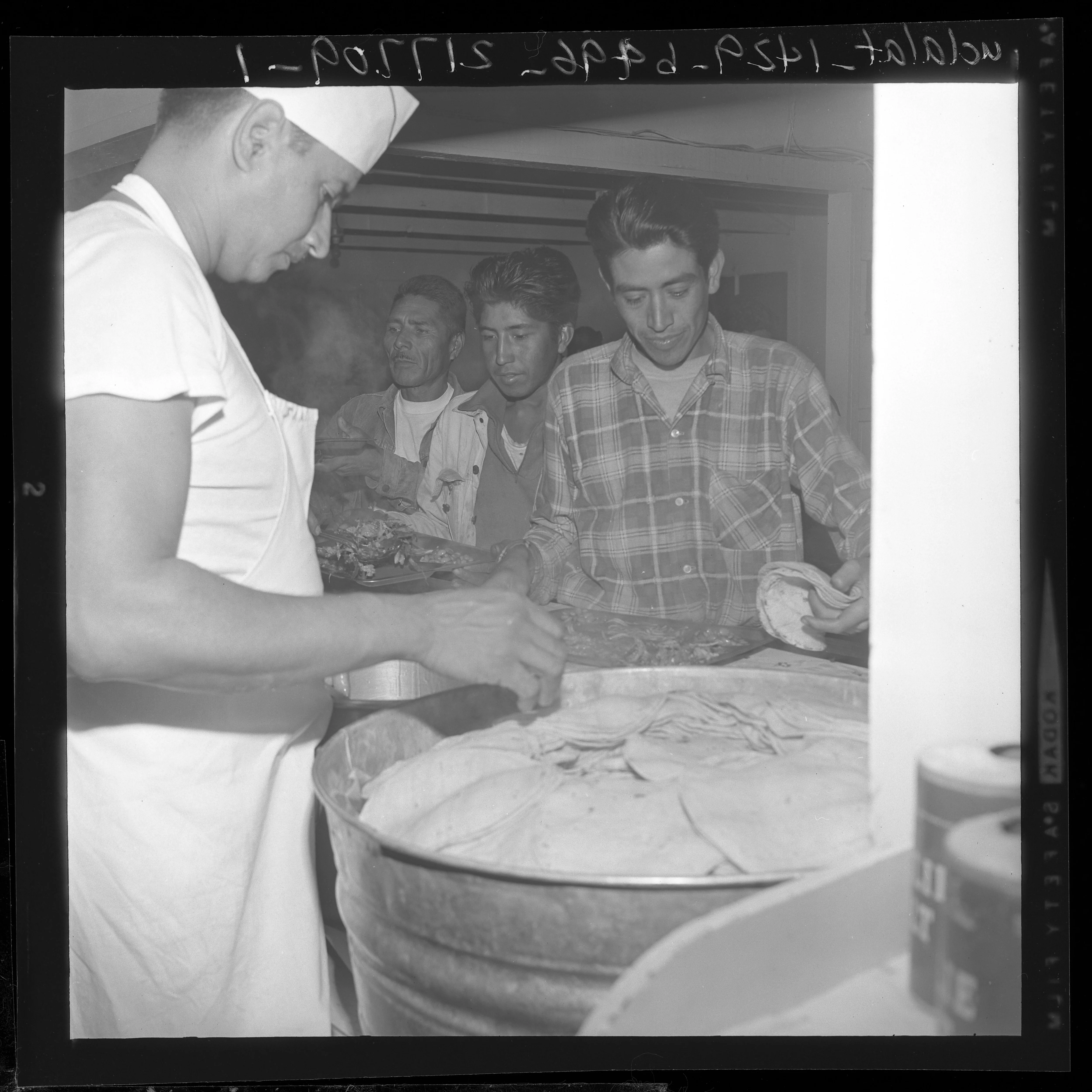

The Bracero Program

From 1942 to 1964, most food production in the U.S. was done by migrants from Mexico known as “braceros.” The Bracero Program allayed fears of a massive wartime labor shortage by allowing for the temporary importation of workers from Mexico as replacements. Ranchers and agricultural growers relied on braceros for “stoop labor” and successfully lobbied for the program’s extension well past the end of the war. Mexican-American journalist Rubén Salazar traveled to the San Luis Rey labor camp in 1962, where the “chow line” served braceros three meals of tortillas and other culturally-relevant foods a day.

Rubén Salazar, “Braceros Cast in Complex Role,” Los Angeles Times, Nov. 26, 1962, p. 3.

Hot Dog, Roy Lichtenstein

Roy Lichtenstein ranks among the most celebrated artists of a postwar movement known as Pop Art, a populist revolt against the high-minded, abstract styles of the prior generation. Starting in 1960, a few commercially trained illustrators began ironically exhibiting paintings to replicate familiar images from advertising, packaging, publishing, and filmmaking. Andy Warhol famously began painting and repainting Campbell’s soup cans. In comic book style, Roy Lichtenstein’s 1964 “Hot Dog” portrayed a quintessential summer snack as heroic — or villainous — as a comic book character.

American Diet

Boosted by the benefits of the G.I. Bill after the war, many white veterans and their families settled permanently in sprawling new suburbs around cities. The geographic ties many families previously had to their home communities and regional customs were broken, eroding cultural and regional food traditions in favor of widespread adoption of the “Standard American Diet” (SAD).

The SAD had its roots in rural, Midwestern, middle-class life, centered on beef, dairy, and wheat production. New federal nutrition standards made these staple foods foundational parts of the military food system delivering nutritious meals to deployed troops. Food technologies developed during the war made it possible to produce and deliver those meals efficiently and cheaply.

The SAD also played a key role in the postwar economy, with Americans relying more on processed and prepared foods like canned, boxed, and frozen meals that were heated and served at home. Advertisers hailed the ideal consumer as a white, stay-at-home wife who relished in new homemaking technologies, and popular television validated this gendered myth of mass domesticity. But many women worked as well — both in the traditional workforce and in domestic roles. Access to the SAD was limited among the most disadvantaged communities of color, and so more distinctive cuisines survived among racialized subgroups mostly living outside the suburbs in the postwar era.

Citations:

Levenstein, Harvey. Paradox of Plenty: A Social History of Eating in Modern America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

During World War II, companies that won military contracts became players in an economically concentrated food system that fed Americans a mass-produced diet of meat, dairy, and starch. While for generations Americans residing in different parts of the country ate in distinctive ways, a new “Standard American Diet” emerged in the postwar years.

Museum Map

WISHING

TREE